The more we can learn about all of Dedham’s residents through the centuries, the better we can tell Dedham’s history.

There was a land hunger in Massachusetts Bay Colony, almost from the beginning. As early as 1634, the Newtown (Cambridge) folk were seeking permission to remove to Connecticut because of a want of accommodation for their cattle as well as a deep-rooted feeling among them that it was a fundamental error, that towns were set off so near to each other. A year later, rumblings were heard of an impending war with the Indigenous peoples; it was all too apparent that the coastal settlements were utterly vulnerable to an attack from the interior. Accordingly, in September of 1635, the General Court issued orders for the establishment of two inland towns, which could relieve the population pressures within the existing settlements along the Bay, as well as serve as a buffer zone between the Indigenous peoples and the main colony. The towns were Concord and Dedham. Concord incorporated the same year and Dedham did so in 1636. Though the original settlers sought to name the town “Contentment,” the name “Dedham” was instead selected, it is thought by the Mass Bay governance, perhaps after the northeast Essex village of Dedham, England.

The land granted to Dedham was in excess of two hundred square miles of virgin wilderness and the original footprint rested on Massachusett and Wampanoag territory. Predominantly yeomen and people from Suffolk, Norfolk, and Essex, England, the Dedham settlers initially contented themselves with remaining close to the area where they landed along what is now the Charles River. Expansion was a process, which came only with time, ultimately resulting in the separation of the following communities: Millis (1649/50), Medfield (1650), Natick (1659), Bellingham, Franklin, Norfolk, Plainville, and Wrentham (1673), Needham (1711), Medway (1713), Walpole (1724), Dover (1784), Norwood (1872), Wellesley (1891), and Westwood (1897). The Reverend John Eliot and his “praying Indians” squatted on Dedham land in what is now Natick. In 1659, after a protracted litigation, the Indigenous peoples were awarded title to those 2,000 acres, and Dedham, in compensation, was granted 8,000 acres at Pocumtuck (Deerfield).

Dedham was spared being attacked during King Philip’s War in 1675-76. Protected to the North by the Charles River, to the South and East by swamp, quagmire, and bog, the main settlement sat upon a broad plateau, which offered a long-range view of all approaches to the settlement. The towns-folk built a garrison, put the town cannon in order, trained their defense forces, and presented such an appearance of preparedness as to presumably thwart attack. Dedham’s offspring in Medfield, Wrentham, and Deerfield were not so fortunate, however. Sensing trouble, the Wrentham folk had abandoned their town and fled back to Dedham; the Indigenous Peoples burned the empty town. Medfield suffered a full-scale attack, which left seventeen people dead. Yet more of the friends and neighbors of Dedham people were killed or carried off into captivity when Philip’s forces sacked Deerfield.

The fourteenth church of Massachusetts Bay Colony was gathered in Dedham in 1638, selecting John Allin as its pastor and John Hunting as Ruling Elder. The church records show no instances of dissension, Quaker or Baptist expulsions, or witchcraft persecutions. On the other hand, the state of peace which existed in town and church should not be surprising in the light of the requirements stipulated by the Town Covenant, signed by all those admitted as settlers:

. . . we shall by al means labor to keep off from us all such as are contrary minded, and accept unto us all such as may be probably be of one heart . . .

Newcomers who seemed to be potentially troublesome, or who posed the possibility of becoming public charges were warned out and forbidden to reside within Dedham boundaries. The whole company, who gathered in general meeting originally, transacted Town business. As the population grew, this became impracticable:

. . . It has been found by long experience that the general meeting of so many men . . . has wasted much time to no small damage & business is thereby nothing furthered . . .

Beginning in 1639, the size of the town was growing enough that selectmen were elected to carry out the administration of town affairs.

On January 2, 1642/3, it was voted at a general meeting of the Town “with an unanimous consent . . . that some portion of land . . . should be set apart for publique use: viz for the Towne, the Church and a fre Schoole.” On November 1, 1644, inhabitants of the Town voted to put funds toward the “maintenance of a Free Schoole in our said Towne . . . and rayse teh summe of Twenty pounds p annu. [per annum] towards the maintaining of a Schoole Mr [master] to keep a free Schoole in our s’d Towne.” In 1647, the Massachusetts General Court enacted the first statute relating to education, likely influenced by the educational experiment in Dedham (a General Court representative from Dedham was one of the overseers of the school). The statute stated that every town with more than fifty households shall appoint a Town member to educate the children to read and write. The basis for education was stated as follows: “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures”; thus the ability to read provided the tools to read the bible, which became a component of the school day.

The Revolution, occurring a full two generations later, made much less of an impact on Dedham. Almost every townsman who was physically fit reported for duty in the Concord/Lexington alarm; a substantial number did garrison duty around Boston; and a few went off on the Ticonderoga Expedition. As the war moved south, however, town involvement rapidly decreased. The town quickly ran through her available manpower pool, and, when issued a quota for the Continental Army, the town had to hire mercenaries from Boston to fill her allotment. The major impact of the Revolution upon the town lay in the sphere of political education and experience. In 1774, a “Meeting of Delegates of every Town and District” in the county of Suffolk (Dedham was not declared the seat of Norfolk County until 1793) was held “at the House of Mr. Richard Woodward of Dedham,” followed by a meeting in Milton (citation: “Supplement to the Massachusetts-Gazette,” September 15, 1774). Woodward’s house was the scene of a Suffolk County Convention, called to protest the Coercive Acts and the deteriorating relationship between Britain and the Colony. What became known as the Suffolk Resolves was approved by the committee on September 9th, 1774 and carried by Paul Revere to Philadelphia, where the Congress unanimously passed them. As the war dragged on, the town, through necessity, developed an increasingly independent governmental process, to provide a system of supply for those commodities the town was obliged to produce for army use, as well as to take up the slack in control left by a primarily military-oriented Provincial Congress.

The Reverend Jason Haven, the younger Nathaniel Ames, his brother Fisher (he and his brother were on opposite political spectrums; the former a Republican and the latter a Federalist), and the Samuel Dexters (father and son) all received their political indoctrinations in Dedham during this period of turmoil and change; it was to their leadership that the town turned in the first generation of American independence. Fisher Ames (1758-1808), for instance, a lawyer graduated from Harvard in 1774, attended the Concord Convention that met during the Revolution in response to the dissolution of Colonial Government by the General Court of Massachusetts, and attended the Massachusetts Ratifying Convention in 1788 where he argued for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. As a state legislator, he defeated John Adams and was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives the same year, being re-elected in 1790, 1792, and 1794. His oratory skills helped gain ratification of the Federal Constitution, he helped write the First Amendment, and his passionate speech led to the passing of the Jay Treaty of 1794. He retired from Congress due to ill health, returning to Dedham to continue his law practice. His brother Nathaniel, a Republican and at political odds with Fisher, other residents including Benjamin Fairbanks, all spurred on by a war veteran from Connecticut, David Brown, an itinerant evangelist for Jeffersonian Republicanism, erected a Liberty Pole in support of Republican ideals. A sign placed at the top read: “No Stamp act; no sedition; no alien bill; no land tax. Downfall to the tyrants of America; peace and retirement to the President [George Washington]; long live the vice President [Thomas Jefferson] and the minority, may moral virtue be the basis of civil government.” Fairbanks was arrested for violating the Sedition Act of 1798, signed into law by then Federalist president John Adams; among its four laws, it made it a crime to speak out against the federal government; the act expired in 1801, three days before the election of Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson.

In 1793, Dedham was selected as the shire town for the new County of Norfolk, and an influx of lawyers, politicians, and people on county business forced the town to abandon its traditional insularity and its habitual distrust of newcomers. The Norfolk and Bristol Turnpike was run through Dedham in 1803, providing a main route between Boston and Providence. One year later, the Hartford and Dedham Turnpike was chartered, serving as a main road through to Connecticut. New taverns were established in Dedham, to provide for the wants of the traveler, but more particularly to provide way stations and relay points for the new stage lines that the turnpike had suddenly made feasible.

In 1835, the Boston and Providence Railroad built a branch from Dedham to Readville, connecting with the main line from Boston to Providence. This was followed, in 1848, by the Norfolk County Railroad, which ran from Dedham to Walpole. In 1854, the Boston and New York Central ran through town, and on to Blackstone. Dedham, almost involuntarily, became a transportation center, and the existence of quick freight service promoted a burst of industrial development.

Mother Brook, dug through from the Charles River to East Brook in 1637, provided a connection with the Neponset River and a source of waterpower for the town’s all-important corn mill. In subsequent generations, that same waterway provided power to roll copper for American coins, to make paper (in three different mills), to support a brush factory and a wire factory, and to run the first water-driven broad powered loom in America, introduced from England by merchant Benjamin Bussey (1757-1842) for his woolen mills. These industries, combined with other enterprises around the town, gave a tremendous economic impetus to Dedham. By 1845, the town’s manufactories employed over 650 people, and produced such varied goods as cotton, cotton thread, woolens, silk, brooms, furnaces, shovels and hoes, paper, chairs and cabinets, tin ware, sheet iron, vehicles, boots, shoes, saddles and harnesses, cigars, pocket notebooks, and marbled papers.

Gradually, the local industries succumbed to economic pressures; the last to go were the textile companies of East Dedham, which fell victim to the economic slump following the First World War. Concurrently, the town fell away from its traditional associations with agriculture; increased mobility for local residents, and an increased rate of immigration by newcomers spelled the inevitable destruction of open, agricultural areas. The Whiting Farm was the first large subdivision, becoming Oakdale in 1871. The Farrington Farm became Endicott in 1872, and the Turner/Whiting tract became Ashcroft in 1873. By 1910, the old Bullard lands near Wigwam Pond had become Fairbanks Park, and the Bingham Farm in Dedham Island had become Charles River Heights and Charles River Terrace. The old Sprague Farm became the Manor, and, almost the last to go, parts of the ancient Smith Farm became Greenlodge Estates.

People of all ages are affected by COVID-19. DHS history teacher Michael Medeiros asked students to submit journals of their experiences during the end of their 2019-2020 academic year. Read a selection of those stories

Thank you to Mr. Medeiros and to the students who gave permission to share their history.

The story of Lillian Wood (1893-1946) “A Life Overshadowed by Disease.”

Every stage of Lillian’s life was overshadowed by disease, yet throughout, Lillian rallied. Her legacy to her descendants is that she tenaciously rewove her heartache into her life’s fabric, a fabric that was textured with hope and love.

Thank you to Sally Seurfert Holmes for sharing Lillian’s story.

Members of four multi-racial Dedham families share their experiences on an episode of “I am Dedham,” a program about Dedham residents. A central message is: “I hear you.” Thank you to Dedham TV and to Joseph Borsellino of the Dedham Human Rights Commission.

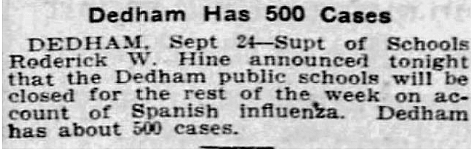

One Dedham family’s story of life during the 1918 influenza pandemic, with comparisons and contrasts to the COVID-19 pandemic of today.

One Man’s Experience of how an individual can contribute to history.

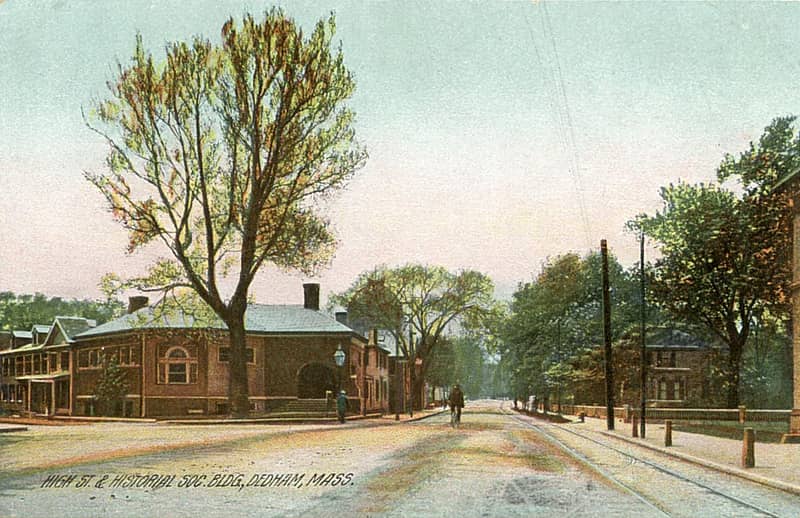

The Schortmann Insurance building opened in 1892 and is one of the most significant landmarks in Dedham Square. To learn more, read an article by Judy Neiswander published in the November 8, 2019 issue of the Dedham Times.

The history of the Black community in Dedham stretches through the centuries.

Dedham’s church community has made significant contributions to the town’s and nation’s history.

The original footprint of Dedham rested on Massachusett and Wampanoag territory.

Immigrants have and continue to contribute to Dedham’s history.

Incorporated in 1636, Dedham was one of the two first settlements established outside of Boston.